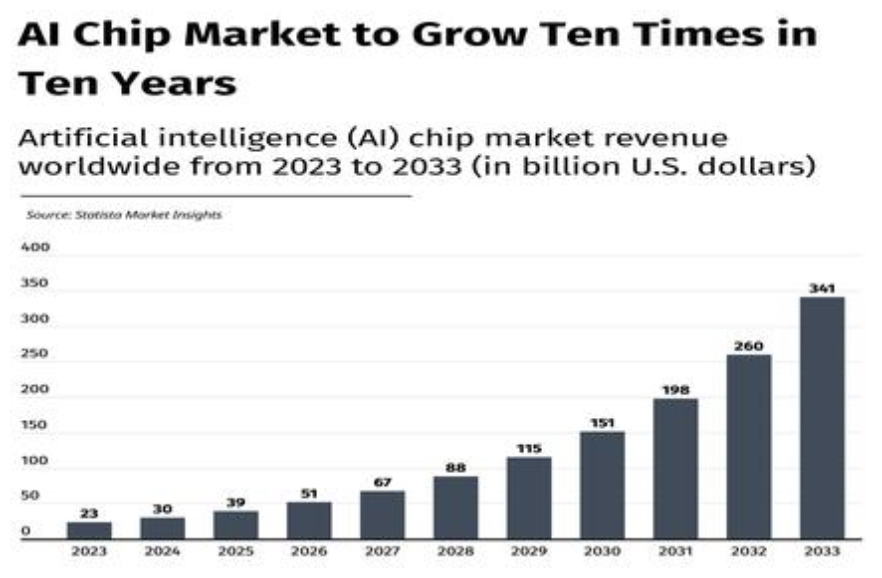

How Hard Is the Semiconductor Industry?

The semiconductor sector is not only competitive; it stands out as one of the most technologically complex and investment-heavy industries in the world. Every tiny semiconductor chip contains a variety of difficulties that stretch the limits of scientific understanding, engineering skills, and global teamwork.Recognizing these intricate issues helps to explain why semiconductors are referred to as the "black gold of the modern age."

Manufacturing: A Dance of Exactness

Establishing a chip fabrication facility is comparable to assembling an orbital station on Earth. These fabs necessitate an atmosphere so immaculate that it is 10,000 times cleaner than what is found in a surgical suite; even a single speck of dust can spoil an entire batch of chips. The lithography systems employed to engrave circuits come at a cost exceeding $150 million apiece and utilize ultraviolet radiation with wavelengths smaller than those of X-rays to create patterns on silicon wafers. Each individual chip undergoes more than 1,000 manufacturing processes, with precision levels gauged in picometers—smaller than a hydrogen atom's width.

R&D: Spending Billions for Tiny Advancements

Progressing in chip technology resembles a lengthy financial race. The creation of a new chip node (for instance, transitioning from 5nm to 3nm) demands investment ranging from $5 to $10 billion solely in research and development. Companies must allocate resources to studies in quantum physics, materials science, and software solutions just to fit additional transistors onto each chip. Nonetheless, success remains uncertain—numerous promising technologies fail to transition from laboratory development to large-scale production, resulting in substantial financial losses.

A single chip is dependent on parts sourced from numerous nations. Rare earth elements are imported from China, high-purity silicon is supplied by the United States, lithography equipment hails from the Netherlands, and advanced packaging is produced in Taiwan. Any disruptions, whether due to natural calamities, trade disputes, or health emergencies, can halt production entirely. For instance, a fire in 2021 at a semiconductor material factory in Japan led to a global deficit in photoresist, resulting in production delays spanning several months.

Talent: Searching for Quantum Experts

The sector is experiencing a significant shortage of skilled labor. Experts in quantum computing, semiconductor physics, and advanced engineering are in high demand, requiring a decade or more to become proficient. Leading chip engineers are lured away with lucrative seven-figure pay packages and stock options, yet this is insufficient to meet the need. Educational organizations are struggling to stay aligned with the swift progress in technology, leading to a gap between scholarly research and the needs of the business sector.

Moore’s Law: Approaching the Limit

Moore’s Law—the assertion that the density of transistors doubles every two years—is nearing its limits. At 3nm and lower, quantum tunneling introduces complications: electrons unintentionally flow between transistors, leading to inaccuracies. Engineers are tasked with devising new designs (such as 3D stacking) and materials to continue progress, yet each solution increases complexity and expense. The moment when silicon chips can no longer be miniaturized is swiftly approaching, compelling the industry to undergo significant transformation.

The semiconductor industry finds itself entangled in the complexities of global geopolitics. Export regulations limit the distribution of cutting-edge chips and manufacturing machinery to specific nations, compelling companies to modify their products for various markets. Adhering to these regulations necessitates teams of legal and trade professionals to maneuver through the rules established by the United States, European Union, China, and others. A solitary miscalculation can lead to billions in penalties or the loss of access to crucial markets.

(Writer:Dick)